From “We Are the World” to the Collapse of Compassion

Forty Years after Ethiopia’s Great Famine, global indifference threatens millions. Can empathy be rekindled?

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

We are the world, we are the children

We are the ones who make a brighter day

So let’s start giving

There's a choice we're making

We're saving our own lives

It's true we'll make a better day

Just you and me

(Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Quincy Jones March 7, 1985 USA for the historic collaborative appeal to the world to support the starving in Ethiopia).

The Great Famine and Universal Empathy

Forty years ago, Ethiopia was devastated by the Great Famine, brought about by natural disaster and human indifference. In a country where the vast majority of people live on what they grow year-to-year, when the rains fail, it means hard times. When the leadership ignores the situation, it is a death sentence. When the international community also looks away, it is the end of the world as they know it.

Famine is never far away in the Horn of Africa, but advanced planning and generous governments can avert the worst. In 1984, however, Ethiopia’s Marxist regime had alienated the West, and worries about the spread of communism gave donor governments pause. Why should they feed a country spitting poison at them every day? As the government official in charge of famine relief, I tried to walk the tight wire of convincing the West to help while at the same time staying on the good side of a dictator who wanted nothing to do with the West and who denied there was a famine at all.

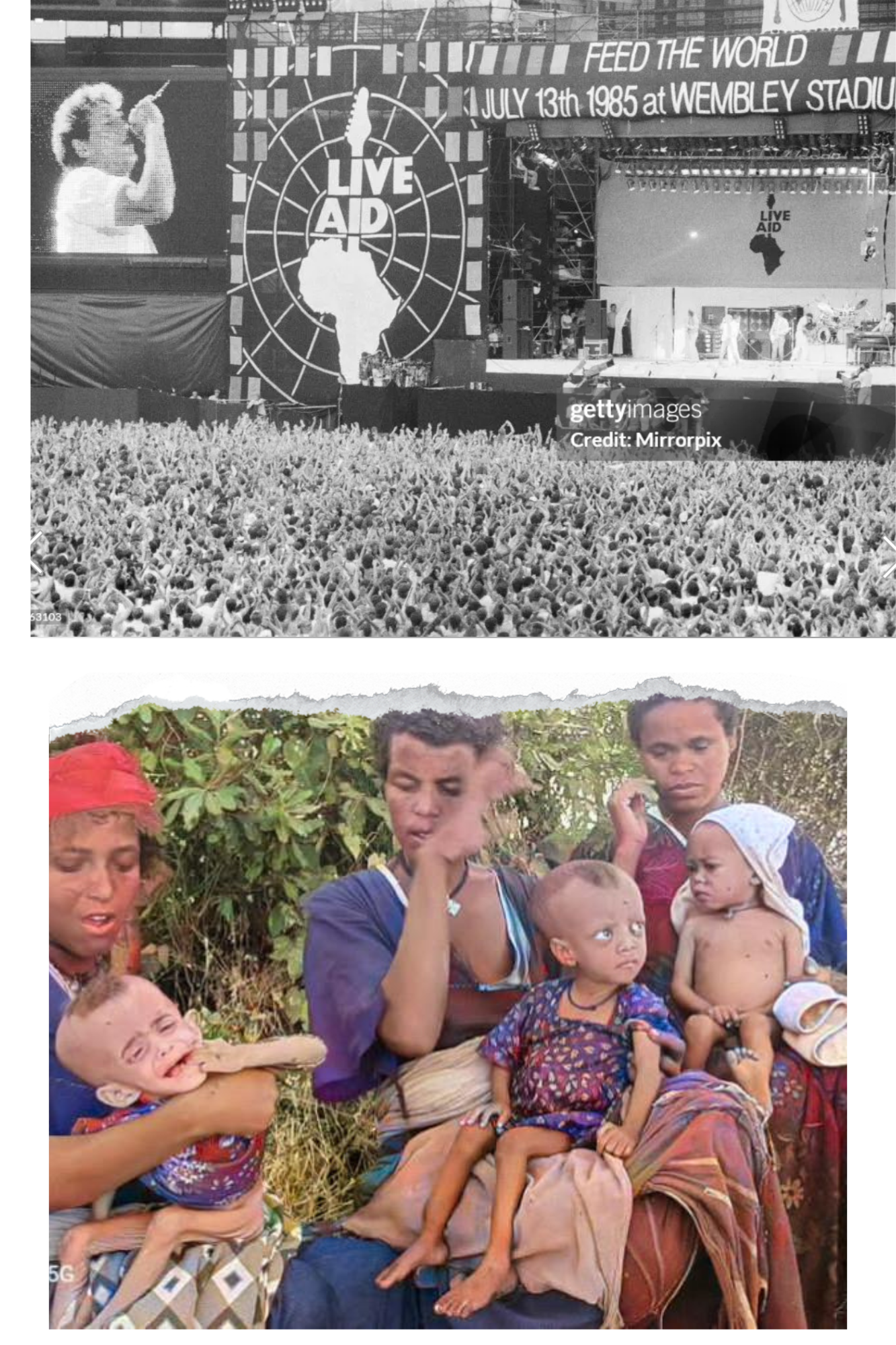

Although the build-up to the famine had been covered by some news outlets, everything changed on October 23, 1984, when the BBC broadcast a second television news report by Michael Buerk, which was subsequently seen by an estimated 470 million people around the world. Filmed at a relief camp overwhelmed with dying refugees, his report was not about politics, but people—starving men, women, and children, many of whom would be dead by the time the footage was shown. Buerk called it ‘a biblical famine’, ‘the closest thing to hell on earth’, and described ‘wasted people …, dulled by hunger, driven beyond the point of desperation’. His unforgettable words and the horrifying imagery from cameraman Mo Amin turned a forgotten tragedy into a global crusade.

Recently, Baroness Featherstone in the British House of Lords paid tribute to Buerk and Amin:

“… the nation was shocked by Michael Buerk’s famous BBC broadcast. It was a watershed moment in TV and world history that alerted the world to the terrible famine in Ethiopia. Close to 8 million people became famine victims during the drought of 1984, and more than 1 million died. It was a broadcast that woke millions of people across the world to both the suffering of the people and the scale of the inequities across the world. It was transmitted by 425 television stations worldwide and gave birth to world fundraising in a way that we had never seen before….It galvanized a whole generation into action.”

Her powerful words are still too tame. Seeing the suffering of those emaciated men, women, and especially children, dying not by the hundreds, but by the millions, was a soul-shattering experience in 1984. The world woke up. The suffering touched everyone who watched, to the bottom of their hearts. People wanted to do something. Contributions poured in, first from individuals, and then from governments that up to then had held back.

Thousands of letters were sent to our office from ordinary people across the world responding to this 23-minute documentary. Here are some examples:

A woman sent a check along with this letter:

“I have been trying to quit smoking for a long time. When I saw your program, I realized how much I really spend on unnecessary things such as this. I have not bought a pack of cigarettes since. Every day I think about smoking, I think of that starving child who needs that money a lot worse than I need those cigarettes.”

Someone from Hull, Ontario with a drinking problem wrote expressing his desire to help a child:

“Now it makes me feel good because I am helping someone with the money I used to drink with, and it is going to good use, and at the same time, I am helping myself, and now I have an extra person to care for, and I am proud to care for.”

A cancer patient wrote:

“I am a cancer patient and am now on disability. Although my disease is dreadful, at least when required, I have good, clean medical care, not to mention daily nutrition. Somehow, it seemed my problem faded away when I saw those helpless people on the screen.”

From Madoe, Ontario:

“I hesitated at sending this amount (the contribution enclosed), which I know seems very small, but to me is quite a bit as I only have my pensions. I don’t have things in my home like other people, not even plumbing, but I am thankful for what I have. I have always found that one never loses by giving.”

An 11-year-old Japanese boy from Japan sent a check:

“I watched Life in Ethiopia on TV on Oct. 23, and I want to give happiness to these people, and I am sending herewith an allowance I got…I send the money because the later I buy, the better the record player will be made …but people’s needs cannot be postponed.”

It was such a relief for me and my agency to know that after months of warnings, help was on the way, not just from individuals but from the highest-ranking leaders in the world. When Mother Teresa came to Ethiopia and saw how enormous the problem was, she got on the phone to President Ronald Reagan, and in my presence, requested his urgent assistance, reading him a list of needs that I had given her. He agreed immediately. “We can’t help everyone. But everyone can help someone,” he said.

On November 4th, I addressed the UN General Assembly:

…one cannot help being moved by the sight of human suffering depicted in [the film]. Even governments that were hitherto less than forthcoming are now following the humanitarian example of their public. We in Ethiopia are particularly touched by the goodwill and generosity shown by ordinary men and women. All this renews our faith in humanity, reinforces our confidence in international solidarity, and indeed encourages us to try even the impossible to save the lives of our unfortunate brothers and sisters.

Eventually, we received more than we could handle. We indeed were the world.

Just before I fled from Ethiopia for good, I addressed the international community:

Through our combined efforts, the drought victims in Ethiopia have been saved from starvation and death. Yet more importantly, the world has learned a historic lesson that there is the will and the determination, humanity can be saved from any disaster of whatever magnitude and complexity. … Compassion has prevailed over politics, and the world has assisted the RRC [Relief and Rehabilitation Commission] in discharging its responsibilities towards the most unfortunate sections of Ethiopian society in an honorable and historic manner.

“In 1985, compassion knew no borders, ideology, or race. Today, empathy itself is at risk of extinction.” Major Dawit Wolde Giorgis

Since then, I have seen people going out of their way to save the lives of others under difficult circumstances, but never in my long experience working in Africa and observing the world on fire have I seen the overflow of empathy and compassion like in the crisis in Ethiopia in 1983-85. The response was universal and massive and brought together enemies and allies in one operation to save the lives of Ethiopians in a super-charged political atmosphere. The world broke all the barriers that divided it and poured out whatever it had to help the poor and the dying.

Most of us are busy caring for ourselves and our families, so special people and special tools are needed to trigger a response like the one in 1985 that brought two worlds together, the East and West, bitterly divided by ideology and on the brink of a third world war. “We Are the World” helped enormously in galvanizing the feelings of people across the globe in a transcendent moment that stands as a testimony to the power of compassion, that most basic and natural of human traits. It taught a lesson to the world that together we can cross borders established by greed and politics, defy bad leaders, and reach out to people denied help by those leaders. Iron curtains and ideological barriers crumble before the power of compassion. But that was then.

The Collapse of Compassion

Since that time, so many more people around the world have suffered and perished in so many horrible ways. I have spent a lifetime in conflict areas with people in dire need of humanitarian assistance. I was in Rwanda during and after the genocide. I was in Somalia, Liberia, Darfur, South Sudan, and Angola, where I witnessed brutal, pitiless civil wars and suffering, sometimes even more severe than what I saw in Ethiopia. My heart aches to see the man-made troubles of Africa continue unabated, but to my even greater sorrow, I am now witnessing the end of an era in which compassion is a universal value. So much suffering and death, so much starvation and disease, so much need, but never the kind of response we saw in 1985.

“The world once responded to human suffering with overwhelming generosity. Today, numbness and apathy prevail.” Major Dawit Wolde Giorgis

Where has compassion gone? Millions upon millions of innocent people are at risk, afraid, suffering, with lives cut short through no fault of their own, and the world looks away. Why? Psychologists tell us that when the scale is too great to comprehend, there is a “Collapse of Compassion,” a tendency to turn away from the intensity of mass suffering. As the number of victims in a tragedy increases, our empathy dramatically decreases, perhaps subconsciously, in a kind of psychic numbing. A quote often attributed to Joseph Stalin sums up this tendency: “One death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.” We must reject this kind of thinking as nothing short of a devaluation of human life.

Empathy, the concern and care for others’ feelings, is a virtue we seek to instill in our children, yet it is sorely lacking in many adults today. One might assume that with an increase in global awareness, empathy would increase, however, this is not what we see. Empathy and concern for “others” have drastically declined across the globe, but unfortunately, most of all in the Western world, where the capacity to know about others in dire need and the capacity to give readily exist. Narcissism is on the rise in America. That may seem unfair to say, but there is convincing evidence to back up the notion that Americans are caring less for others and more about themselves, for example, in studies from Indiana University’s Program on Empathy and Altruism Research.

Further evidence can be found in Professor of Psychology Jean M. Twenge’s book Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled — and More Miserable Than Ever Before, where she writes that “the generations, especially those born in the 1980s and 1990s (often associated with millennials), display higher levels of self-esteem, narcissism, and entitlement, all great personal traits if one wants to accelerate empathy erosion and increased societal polarization.” This is the very period when the parents of those millennials were showing the greatest empathy in contemporary world history in their response to the 1984-85 famine crisis in Ethiopia.

What happened? Twenge points out that societal shifts, such as an increased focus on individualism and the self-esteem movement in education and parenting, could be factors contributing to this phenomenon. Another factor is that more people are living more isolated lives, along with traditional and religious values being put aside. They associate only with who and what they like without having or feeling the obligation to know about others outside their bubble.

Furthermore, the rise of social media and the instant gratification it often brings can exacerbate feelings of entitlement and the loss of empathy. According to a study from the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology:

“The use of social media, which has exploded in the past decade, has fostered the creation of echo chambers where people are exposed primarily to information that aligns with their existing beliefs. This minimizes exposure to diverse perspectives, leading to further polarization. It’s less about whether we agree or not about something, it is also that fewer have any real physical friends to agree or disagree with.”

“When politics replaces empathy, innocent lives become statistics, and the cries of millions vanish unheard into digital echo chambers.” Major Dawit Wolde Giorgis

The collapse of compassion is not just about the numbers involved, it is about empathy fatigue, whose key characteristics are desensitization and burnout. Endless exposure to the suffering ‘of others, in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and parts of Latin America where millions suffer and die because of lack of basic needs that the Global North has in abundance has led to emotional exhaustion and feelings of numbness, indifference, and an inability to care about the suffering of others.

Greed is also a factor in the collapse of compassion. Western conservative ideology favors smaller government and greater power to the private sector, managed by individuals with no obligation to the welfare of the people. The repercussions of these policies are disruptions of social bonds and welfare societies. It also means that for the last several decades, since the fall of communism and socialism, Western nations have once again exploited the poor in their own countries and plundered resources from countries that are today the poorest places on earth.

The damage greed has done cannot be overstated. Foreign and non-state actors, including private and multi-national companies, rebel groups, and transnational networks, play a significant role in conflict zones and mineral-rich regions of Africa. These actors can exploit resources, fund conflicts, and undermine state authority, often exacerbating violence and instability to enable uncontrolled looting of precious minerals.

In some cases, it is not about minerals, but rather about the strategic importance of a particular country. In such cases, non-state foreign actors in collusion with local military, rebel groups, or state officials undermine the political status quo to ensure that it conforms to the interests of a particular foreign government. This is a strategy used mostly by the great powers but nowadays also by smaller players like Iran, the UAE, Turkey, and others.

In 1984- 85, when the world responded so overwhelmingly to the needs of the famine victims of Ethiopia, the power behind this remarkable response in the Western world was not the various governments, but the people. The Ethiopian regime was a Marxist government aligned with the Soviet Union, and for the Western world, the famine was a tool that could be used to overthrow that regime: let the famine run its course, and the suffering would discredit the communists. But the public response defeated that purpose. The pressure from the public was so intense and so broad that, ironically, it would have caused the fall (through the ballot box) of some Western governments had they not responded in the way they did.

The tremendous assistance from government agencies turned the tide in 1985. At that time, USAID was the lead international agency in the operation to save lives. In the UK, the Department for International Development and similar government agencies in the capitalist world were hard at work as well, and admired everywhere. The help they gave cannot be overstated, and anyone who received that aid is forever grateful. It was an example of “soft power”: America’s image did not suffer by helping people under a communist regime. All that USAID gave boosted the image of the American public as humane and compassionate. All of us won then.

However, in the last decade, a struggle began to reduce government spending and strengthen the private sector– in other words, to make the rich richer at the expense of the poor. In the UK, the Conservatives shut down the highly successful Department for International Development in 2020, to the sorrow of humanitarian workers everywhere. This movement reached its climax this year with the re-election of Trump. His administration has, in effect, become a tribunal where millions of the most needy have been condemned to death. USAID has faced enormous cuts in its humanitarian and lifesaving programs—83% !– in an attempt to save the US taxpayers money. This means an end to programs aimed at combating HIV and AIDS, among many other things. The USA has also left the World Health Organization, where its contributions have saved millions from deadly diseases, and it has flip-flopped on funding for the World Food Program, where it was by far the largest donor. The confusion created by the administration has jeopardized the operations of dozens of agencies working to save lives. The Trump administration has also stopped funding for programs that focus on women’s reproductive rights, dooming many poor women to unwanted pregnancies and loss of medical facilities for difficult births.

Nothing is more depressing than Trump’s announced plan to eliminate the entire Bureau of African Affairs in the State Department, following his campaign promise to “put America first.” This is as much as to say “Africans don’t matter–let them starve, let them die,” and he now has no hesitation in revealing that what he really means by his well-known slogan–“make America great again”– is to “make America wealthy again.” His measure of “greatness” is the size of a bank account. Compare this with the America of 1985, for whom a “great country” did all it could to help those in need, following the ideals that its greatest leaders espoused throughout its history and which the rest of the world admired and emulated. It is hard to imagine a more grotesque contrast, as the United States is not serving its best interests in Africa, and its policies drive governments straight into the arms of China.

To sum up: after three decades of the Cold War ended and the United States dominated the world scene as a unipolar power, its humanitarian stance about the Global South appears to have transformed into a far more complex system of geopolitics. It is not humane. It is selfish. It is exploitative. It is greedy. It is insensitive to the sufferings of others unless you are from the white Global North. The architects of the emerging political order practice empathy only when it serves the interest of political elites and business corporations. As Frans De Waal puts it in his book The Age of Empathy, “Human we are, and humane as well, but the idea that the latter may be older than the former, that our kindness is part of a much larger picture, still has to catch on,”

If it does not “catch on,” if the path the Global North is following does not change, it is all too clear what will happen: 2025 will be a year of suffering and death such as has not been seen since 1984. The impact in Africa will be felt most acutely in Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, CAR, and Somalia, all facing conflicts, displacement, and food insecurity that jeopardize the lives of millions. Specifically:

The Amhara genocide and crimes against humanity that the Western world refuses to expose.

I have been part of a team of experts that has documented this genocide in detail and brought it to the front doors of the ICC, but the world has yet to acknowledge and support the effort to stop it. Genocide is a strong word, and some have argued it does not apply, but as an international lawyer from Columbia University who has documented some of the atrocities, when I say “genocide” and “crimes against humanity”are being committed in the Amhara region, it is because they are true. I have been to the ICC and have attended cases in the Arusha Tribunal for the genocide in Rwanda.

I have also participated in the reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to bring to justice those who committed war crimes and other atrocities in Liberia after 14 years of war. The mainstream Western media refuse to talk about the crimes being committed in Ethiopia because they feel it has no relevance to strategic US and European interests. Political interests have replaced empathy. It is shameful that the West will not call it “genocide” or “war crimes” unless there is something to be gained politically.

Beyond the atrocities in the Amhara region, the rest of Ethiopia is facing a humanitarian crisis reminiscent of the Great Famine owing to ongoing conflicts, climate change, and health emergencies. Nearly 4.5 million are displaced, a significant portion of whom are children and women. Additionally, Ethiopia hosts over 1 million refugees and asylum seekers. Many of those affected – women, children, and the sick and wounded – have no way to avoid the day-to-day violence. Estimates are in that about 10 million will need assistance, costing $2 billion, with a funding gap of $496 million in the first half of the year.

The humanitarian situation in Somalia is worsening as drought, conflict, and soaring food prices push millions toward extreme hunger. The violent attacks of Islamists exacerbate an already dire situation. The humanitarian crisis in Somalia is worsening as drought, conflict, and soaring food prices push millions toward extreme hunger, UN agencies warned last February.

- One million more Somalis will face crisis levels of food insecurity in the coming months due to worsening drought conditions, conflict, and high food prices.

- An estimated 3.4 million people are already experiencing crisis-levels of hunger. About 1.7 million children are expected to suffer acute malnutrition this year, of whom 460,000 are expected to suffer severe malnutrition.

The war the DRC has been ongoing since independence. Since 1996, conflict in eastern DRC has led to approximately six million deaths. Levels of humanitarian need are enormous and continue to grow yearly: 15.6 million people needed emergency humanitarian assistance in 2020, 19.6 million in 2021, and 27 million in 2022. Measles, cholera, monkeypox, malaria, and Ebola are constant worries. As people live in squalor, flee from attacks, and die in misery, international companies that want the mineral wealth of this enormous country operate freely without the constraints of government bureaucracy because there is no effective government. As an article in the Guardian makes clear, there would be no cell phones without minerals from DRC, sometimes mined in slave-like conditions, yet as multinationals exploit these resources, the local population does not even get back basic food, shelter, and medicines, let alone aid in developing the country. They remain the poorest people on earth.

South Sudan and Sudan

Conflict and insecurity continue to be major drivers of need in South Sudan. The humanitarian crisis persists due to a combination of sporadic armed clashes, inter-communal violence, food insecurity, public health challenges, and climate shocks. These factors have severely affected people’s livelihoods and hindered access to essential services such as water, sanitation, education, and healthcare.9 million people, or roughly 80% of the population, need humanitarian protection and assistance.

Because of its senseless civil war, Sudan has the largest internally displaced population ever reported, with an estimated 9.1 million refugees within the country. In 2024, the economic crisis, ongoing civil war, and widespread flooding further deepened people’s misery. North Darfur has been declared a famine area because of the war with no end in sight. Many have fled to Chad, where UN agencies can’t keep up. Half the population, 25 million people, are now in need of humanitarian assistance. Protection concerns remain particularly high for women and girls, especially those fleeing Sudan, who face extreme safety risks during their journey to South Sudan. Many arrive in poor physical and psychological conditions, having been exposed to sexual violence. As of late December 2024, more than 900,000 people had arrived from Sudan, with projections estimating an additional 337,000 arrivals in 2025. 30.4 million people– two-thirds of the total population–require support, including health, food, and other aid. 25.6 million face crisis-level hunger, going without meals for days at a time, and 638,000 are experiencing hunger at famine levels. As always, the children are hardest hit.

The Central African Republic (CAR) has faced prolonged instability due to years of political, security, and humanitarian crises. In 2025, 2.4 million people (38 % of the population) are extremely vulnerable. These numbers are beyond the scope of any humanitarian aid, so many displaced people have crossed the border into neighboring countries like Cameroon, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In fact, it is believed that one in five Central Africans is either displaced or living in exile at the present moment. Often, these families are extremely vulnerable, lacking adequate food, shelter, and livelihood opportunities. Infrastructure in CAR is poor, health services are sparse, and almost half the population needs humanitarian assistance.

Communities must plan and prepare

Natural disasters will occur. Pandemics are always a possibility. The poor will always be with us. We all know this and know that, consequently, people will need help to survive. It could be any of us, on any continent, at any moment. In the 1984-85 crisis, there was a sudden awakening to the enormity of the danger millions faced, and it was the pressure of the public that forced the government to add to their humble contributions. It was the power of the people that took over then. The world governments had the resources, and they were forced to dispense those resources on behalf of the people.

With the collapse of compassion, it may never again be possible for this kind of “people power” to force governments to act on behalf of the needy, but instead, in several instances, governments themselves have become part of the problem. There is evidence from countries like Singapore that help for the needy works best when governments and organized society systematically and regularly promote volunteerism with incentives of various kinds. As opposed to lurching from crisis to crisis, helping those in need becomes a regular part of life. As the Charities Aid Foundation puts it: “For these success stories to be replicated globally, governments should make it easy to give and support efforts to build resilient civil society organizations. By making sure the right building blocks are in place, we can grow giving and community engagement to work towards a vibrant civil society in every country.”

I believe that compassion is an inherent trait, but it must be nurtured through education, information, and the knowledge that any one of us could some day be on either side–the victim or the savior, and that it is only accidental circumstances that have made us who we are and them who they are.

Am I right in my belief that kindness is an inherent trait, or is it something we learn through experience? Psychologists, social scientists, and other researchers say it’s both. Not only are we predisposed to being kind, but we can also increase our capacity for kindness throughout our lives. As a humanitarian worker, I have, like my colleagues, been driven by empathy and consider compassion a sacred tenet of what it means to be human. But where does compassion come from? In We Are Born to Be Good U.C. Berkeley psychology professor Dacher Keltner writes that the root of compassion “lies in the dependence and vulnerability of our children.” When we are present at the birth of a child, when we hold that helpless baby in our arms and later see them cling to us for support, rely on us for nourishment, or go from tears to a smile at seeing us just walk into a room– a bond is created between us as our hearts go out to that innocent being so dependent on us. Compassion is born with the birth of a child, and the extension of this feeling toward our fellow men and women in need is what every humanitarian worker lives with.

What is the role of Faith?

Faith and empathy are closely related, as many religious traditions emphasize compassion and understanding for others as core values. I grew up and lived with religious and community values that considered helping others or being there for others in their times of need as an important aspect of life and living. These were the ties that bound us to each other. Today, these values are disappearing, especially in the West, as traditional church attendance declines at a rapid pace. This does not mean, however, that those who have left their churches are indifferent to the needy. The generosity of people the world over is evident in this year’s Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) World Giving Index.

“We must revive compassion, not because it’s easy, but because humanity depends on remembering that while we cannot help everyone, each of us can help someone.” Major Dawit Wolde Giorgis

In response to a year of continued economic and humanitarian challenges, the research finds that people from across continents and cultures remain ready to help those in need and that donation levels have increased in certain regions and for specific populations. This might look encouraging, but the facts on the ground in Africa are different. Indeed, the study at the same time shows that it is the size of donations that has increased and not the number of donors. Further, people are more selective about who they give to. This is also borne out by the organization Giving USA. The challenge for charities will be to effectively tap into the compassion inherent in all of us, apart from the organizations that are associated with religious institutions.

American Christians put the Trump administration into the White House, so how do they justify the treatment of migrants and the global poor when the Bible clearly says we must help the poor and needy? Vice-President Vance, who converted to Catholicism several years ago, has justified the current administration’s deportation of migrants and its cutoff of funds for USAID by invoking a Catholic teaching that our first duty is to our families, then to our immediate neighbors, then community, country and finally those far away in the world, which would seem to be an excuse for setting a limit to charity, and would in effect doom the Global South to fend for itself.

Two months earlier, Pope Francis reminded Vance (through a letter to US bishops) that the true meaning of Christian charity is found in the parable of the good Samaritan, in compassion that “builds a fraternity to all without exception” and not in pushing away those who need assistance, wherever they may be. On Easter Sunday, on the eve of his death, Francis summoned his last strength to meet Vance in the Vatican for a few minutes and pray with him on this subject. Let us hope that Mr. Vance is moved by the Pope’s determination to rise from his deathbed to meet with him as a way to underscore the importance of his message, and that Mr. Vance will take it to heart for real change in Washington.

King Charles of the UK echoed the Pope’s message this year at Easter: “One of the puzzles of our humanity is how we are capable of both great cruelty and great kindness. This paradox of human life runs through the Easter story and in the scenes that daily come before our eyes — at one moment, terrible images of human suffering and, in another, heroic acts in war-torn countries where humanitarians of every kind risk their own lives to protect the lives of others.” We cannot look away—compassion is the central message of all religions.

Role of International Institutions.

All international institutions have an expiration date. During my adult working life since 1965, I have seen the world order zig-zagging between World War Two, a new Western-dominated power, the Cold War, the decolonization of Africa, the dismantling of the Eastern Bloc led by the Soviet Union, the emergence of a unipolar world led by the only superpower, the USA, and currently am about to witness the dismantling of this unipolar world order and the collapse of universal empathy.

“Real greatness is measured not by wealth, but by how we respond to human suffering—because empathy is our natural state, and apathy is a learned condition.” Major Dawit Wolde Giorgis

The establishment of international institutions after the collapse of the League of Nations, such as the United Nations, the Security Council specialized agencies, the ICJ, the European Union, the World Trade Organization, WHO, WFP, IOM, UNHCR, and more recently the ICC have provided global services, and stability by managing conflicts and humanitarian aid in an increasingly complex and interdependent world. Though all these organizations were tilted towards managing the interests of the Western world, they were effective in stopping a slide into another world war, in trying to prevent wars within states and between states, and in providing humanitarian assistance for the displaced, the hungry, and those plagued by war, disease, and poverty.

These institutions are functioning less effectively now, and without them, the Global South is going to endure more suffering. Moreover, some of these institutions are setting up deals with countries that are reminiscent of colonial exploitation. This will continue until the Global South rids itself of a Western-established, greed-based system and replaces it with a more humane order. This will require a great measure of unity and resolve from the countries of the South. Above all, it will demand wise leadership that rejects personality cults, toxic party politics, ethnic division, and corruption. The good models are there for all to see; it just takes leaders who will follow their examples, leaders who will put the needs of their people above personal gain or party influence, who will foster peaceful transitions of power, fair elections, and who will abandon the destructive desire to rule for life. It will also require an educated population who have been taught to nurture the spark of compassion that they are born with and to work towards the betterment of their communities, nations, and the world as a whole, as opposed to personal gain. Only then can the nations of Africa join together to meet the demands of their at-risk populations, free from outside governments and actors who have more interest in making money than saving lives.

Until then, we have to continue to appeal to the international community. We must do all we can to pressure governments everywhere to stop the decline of compassion. With the defunding of UN organizations like the WFP and WHO, the role of the international institutions in providing needed assistance across the world will certainly change enormously. It might not happen instantly, but without a doubt, we are witnessing the end of the international rules-based order and must prepare for the worst.

I leave you the thoughts of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, who wrote that he had three passions:

“…the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind. Love and knowledge, so far as they were possible, led upward toward the heavens. But always, pity brought me back to earth. Echoes of cries of pain reverberate in my heart. Children in famine, victims tortured by oppressors, helpless old people a burden to their sons, and the whole world of loneliness, poverty, and pain make a mockery of what human life should be. I long to alleviate this evil, but I cannot, and I too suffer.”

This has been my life. I have found it worth living, and would gladly live it again with lessons learnt, if the chance were offered me.